Derreennaclogh

Rock art comprises groups of geometric and other abstract motifs, mostly pecked though some are incised, on flat or gently sloping earth-fast boulders and rock outcrops. Occasionally designs are pecked on other existing stone monuments such as orthostats of megalithic tombs, cist roof-stones and standing stones. The association with existing monuments suggests a Bronze Age date but research points to the origins and development of rock art in the Neolithic (O’ Connor 2006-2). While some motifs are similar to those displayed in megalithic art, with the stone tool technology being used, the balance of motifs chosen is quite distinct, with cupmarks (pecked hemispherical depressions), cup and ring marks, cup and concentric rings with a line or groove running radially from the centre through the concentric rings, discrete straight and curved lines sometimes forming grid-like patterns favoured in rock art (Finlay and Harris, 2017). Compositions can be dense or widely spaced, individual motifs can be linked or not, panels can extend over natural edges and breaks in the stone or not. This is a type of monument common across Atlantic Europe, the coastal seaboard on the western side of the European continent, extending from the Iberian peninsula through France and the British Isles through to Northern Europe and Scandanavia. In Ireland (Republic) rock art is widely distributed with 736 known examples with distinctive clustering in counties Donegal, Cork and Kerry, Wicklow and Carlow, Louth and Monaghan.

This abstract form of art is obscure in its meaning but is an outdoor art form where context and landscape location have significance. As many of the monuments share some locational characteristics being found in elevated locations enjoying prominent views rock art can be seen to imbue the surroundings with significance. Some archaeologists suggest that these monuments may mark territorial boundaries or routeways through the landscape. Rock art may be utilised to track movements of the sun, planets or stars through the year (Finlay and Harris 2017, 172). Considerable research is being carried out in University College Cork and more recently University College Dublin, with many additional monuments being uncovered by active field workers or those working on State commissioned surveys.

Depending on the weather, be it a grey overcast day, or those rare Irish sunny days, and the time of day the viewer will experience a variety of aspects of when looking at this art form. The significance to those who pecked these designs into rock surfaces is not understood but with all of the plastic arts it had a significance to the artist who selected and executed the designs, to the viewer who experiences the work and to society: then, as a form of self-expression or ritual practice and now, to us, as a magnificent survivor of millennia of weathering and general attrition, a source of inspiration and enjoyment into the future.

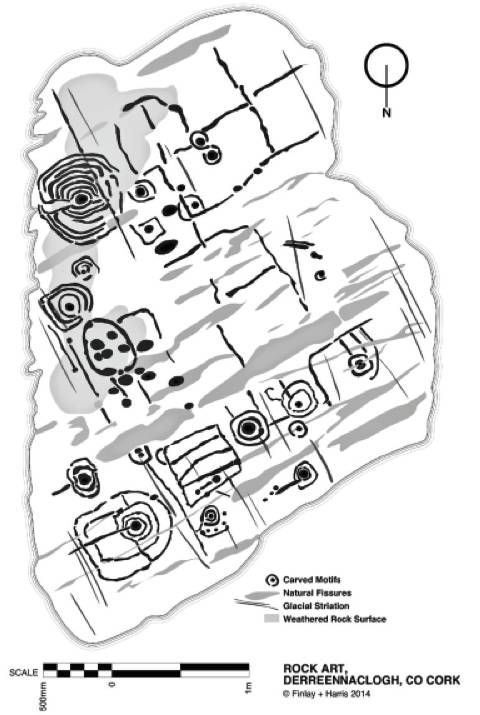

The example presented in Monument of the Month for April is the decoration of a large boulder at Derreennaclogh County Cork. This is situated on a small plateau of a hillock in heath and scrub (110m OD), on the east side of Bawnaknockane River valley; Overlooked by higher ground in the wider vicinity. Mount Gabriel, synonymous with Early Bronze Age mining, is clearly visible in distance to the south-west. There are a number of rock art monuments in the general vicinity. A companion panel, which is in a very worn condition, is just 6m away and there is another decorated rock at a distance of approximately 40m. The monument comprises a very rough and fractured expanse of rock, (dimensions 4.45m north-south; 3.30m east-west), which was fully exposed in relatively recent times, evident by the edge of sod (D 0.12m) around the perimeter. The rock is split and fissured from north-east to south-west while glacial striations run at right angles across these fissures (ibid). It is sub-rectangular in plan, having natural striations and pocked solution marks across its surface. This is an extensively decorated rock art panel with a sub-rectangular decorated surface (dimensions. 4.45mnorth-south; 3.30m east-west) bearing a variety of motifs in size and form. The decorative elements are in a reasonably good condition, albeit having a slight crudeness, possibly due to the rough nature of the stone. There are approximately eleven main motifs and numerous cupmarks, pickmarks and linear grooves (McQueen A and Rahilly V, 2017). Rings are not precisely executed and lines don’t necessarily run straight.

These are grouped triptych-like in three panels, arranged along an axis from north-east to south-west in the same orientation as the natural divisions of the rock surface. The northernmost panel comprises paired and groups of three motifs, comprising cup and ring and cup and two ring motifs with and without radial grooves running outwards from the centre of the cupmarks to the north-east.. Some of the cup-marks are surrounded by sub-rectangular border motifs. One of these designs may be an unfinished rosette design. Some crudely orthogonal grids accompany the basic designs.

The middle panel has the weight of decoration arranged at the north-eastern side of the stone with multiple small cupmarks set within a large oval and extending beyond it, along with cup and two-ring motif within concentric oblong designs. Beyond that to the south-west, are some linear grooves in a grid-like pattern.

The third and final panel at the south consists of a very large intricate cup and eight-ring motif followed to the south-west by a number of linear grid like grooves accompanied by paired and triple cup-marks adjacent or along the length of the linear groove. The cup and eight-ring motif in this case is what has been called a keyhole motif, with the groove extending from the cup-mark formed by the ends of the pennanular rings extending down to form two parallel channels.

Overall the design is busy and dense, particularly at the eastern part of the stone becoming less busy to the west.

This stone has been subject to recording by Alison McQueen and Vera Rahilly for the Archaeological Survey of Ireland (ASI) and detailed research and the production of a wonderful depiction by Finola Finlay and Robert Harris which they have kindly allowed the National Monuments Service to reproduce here.

Image from Finlay and Harris 2017, with kind courtesy of Finola Finlay and Robert Harris.

O’Connor, B., 2006-02, Inscribed Landscapes, Contextualising prehistoric rock art in Ireland, PHD thesis, UCD, Dublin. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/10197/3703.

Finlay, F. and Harris, R. 2017, Rock Art of Derreennaclogh, County Cork. Journal of the Skibbereen and District Historical Society, Volume 13. Available at https://www.academia.edu/34110074/Rock_Art_at_Derreennaclogh_Co_Cork

McQueen A. and Rahilly V. CO131-069---- Sites and Monument Record 2017. Available at https://maps.archaeology.ie/historicenvironment